Author

Updated September 2022

This blog addresses several questions which arise frequently in utilization reviews, peer reviews, and settlement discussions. This is an update on a blog dated February 23, 2021.

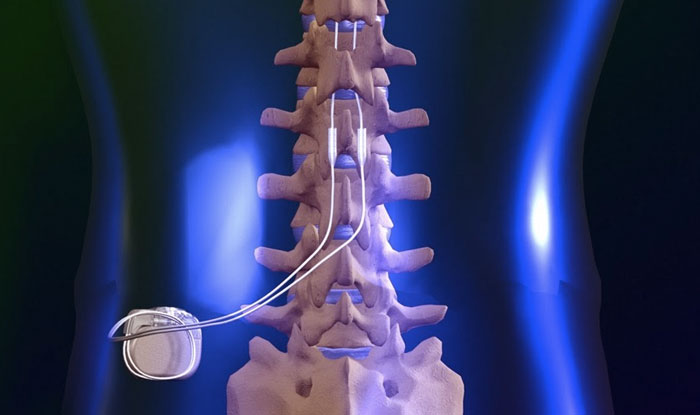

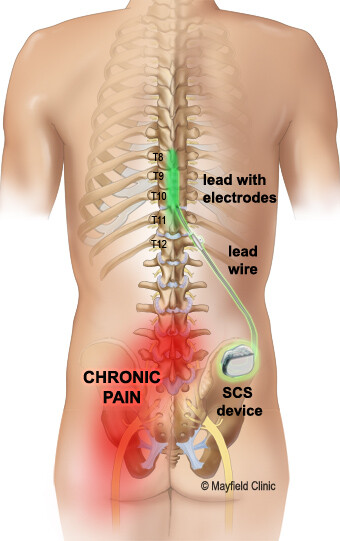

Spinal cord stimulators (SCS) are usually an end-stage treatment for chronic neuropathic pain. The original type of SCS device is called tonic stimulation (traditional low frequency). This device has limited effectiveness, usually with only 50 to 70 percent pain relief. Efficacy decreases over time (by about three years) for about 30 percent of patients, as shown in multiple retrospective studies of patients with failed back surgery syndrome and in a randomized, controlled trial in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) patients.[1] A December 2021 review of 16 studies evaluating SCS for chronic pain relief found the incidence of infection in SCS implantation ranged from 3 to 7 percent, while it ranged from 2 to 31 percent in reoperation/reimplantation procedures.[2] All the studies were at high risk of publication bias.

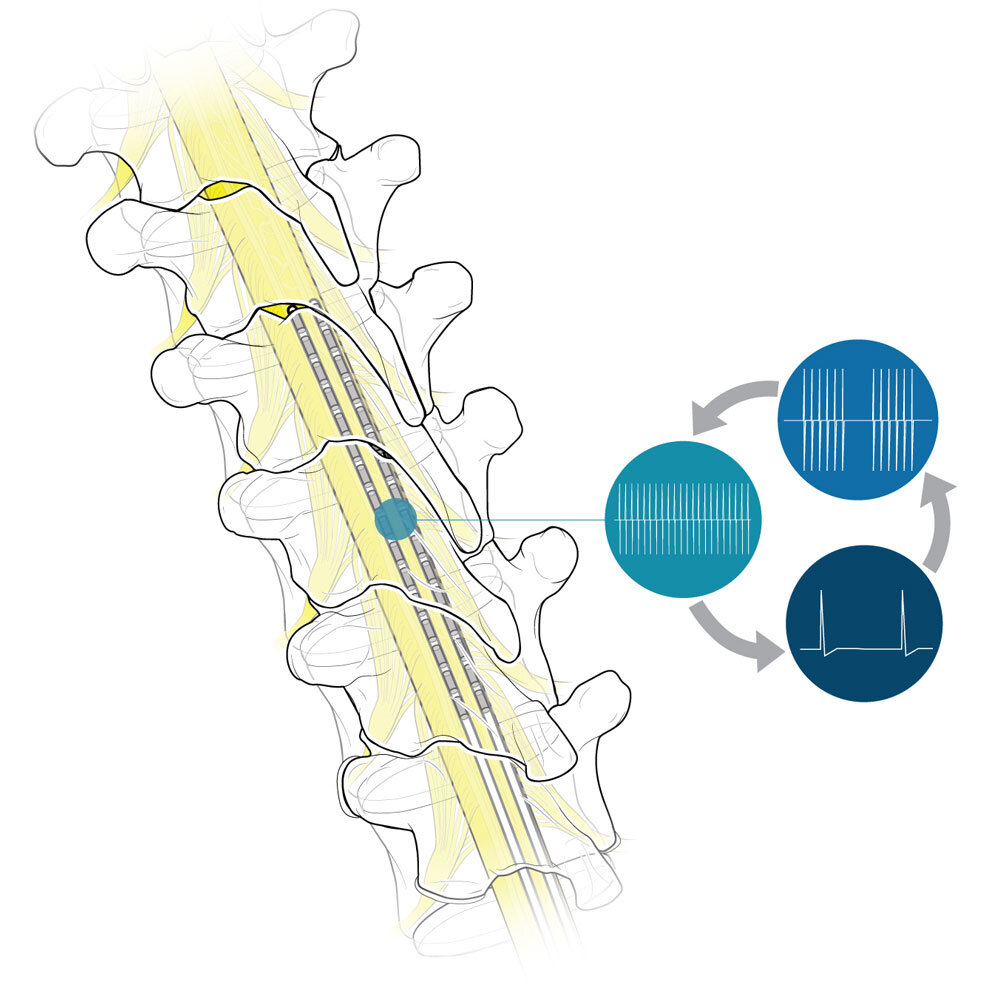

Recently, stimulators using new technology have been introduced, including high-frequency, subthreshold, and burst models. The precise reasons any of these stimulators work remain unknown. The FDA generally uses an abbreviated review process to clear these devices with limited clinical testing, allowing manufacturers to use data from studies of previously cleared stimulators. This is referred to as “substantial equivalence.” The FDA also allows device makers to use supplementary requests to change a device without submitting new data for review. With the introduction of new technology, there are now multiple requests for SCS treatment for indications not previously seen with the original technology.

- Is an SCS recommended to decrease radiculopathy or axial low back pain in patients who have not had spinal surgery?

There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of an SCS in patients with low back pain and/or radiculopathy who have not had a surgical procedure. In August 2021, a systematic review identified studies reporting outcomes of SCS for chronic back pain patients without prior surgery (with or without secondary radicular leg pain).[3] Ten primary studies (sixteen publications) were included. Only one study had data for 36 months, and this study included only twenty patients. All of the eight non-randomized controlled trials reporting pain outcomes had either moderate or serious risk of bias. Many of the studies did not include a comparison/control group. While favorable outcomes were reported in terms of pain reduction and functional improvement in what were primarily short-term studies, not all studies found statistically significant findings. The authors suggested that additional research was needed in this area.

- Can an SCS decrease the use of opioids?

There is no strong evidence to support this claim, and implanting an SCS for this purpose is not currently recommended. While some data show a decrease in opioid intake, this appears to be most likely to occur in patients who were on low doses of opioids before the procedure.[4] Actual weaning off opioids only appears to occur in patients on extremely low doses of opioids pre-procedure (20 to 30 milligrams).[5] Variables associated with reduced odds of weaning off opioids include long-term use of this class of drugs, use of other pain medications, and obesity.[6] Weaning off opioids is a complex psychological and physiological process, and substantial pain relief after any therapy may not strongly correlate with willingness to reduce or actually stop opioid use.[7]

- Is there any evidence for replacing a failed tonic stimulator with a newer waveform model?

This salvage treatment approach should be considered investigational. Published research is primarily from manufacturers or from authors with industry ties, and there are severe limitations in the published studies, including selection criteria, short duration of follow-up (six months or less), and retrospective or case study design. There are no guidelines available on selection of patients with tonic stimulators who will benefit from switching to a waveform device.

A review of SCS salvage therapy was conducted in 2020.[8] It covered eight studies and four abstracts/poster presentations. The conclusion was that conversion from conventional tonic stimulation to burst, high-frequency (10 kHz), multiple-wave forms may be appropriate, but only in select patients. The authors noted limited studies are available, and the subset of patients who might benefit has not been determined. Further research is needed to determine the most appropriate patients. There is a 2020 study on removal of high-frequency (10kHz) SCS in real-world settings.[9] The estimated median time to removal was 3.5 years, and approximately 40 percent of SCS units were removed by 3 years. A high-frequency unit was implanted in place of a failed conventional SCS device in 66 percent of patients, indicating both the conventional SCS treatment and the high-frequency replacement had limited success.

- Is it recommended to perform a repeat trial in patients who have failed an initial SCS trial?

Currently, another SCS trial is not recommended after a failed trial of any type of SCS. This is fairly obvious, based on the fact that a switch to other forms of stimulation remains investigational. Research on repeat trials, particularly those that involve switching to another type of device, is also in the preliminary stage. Some authors are beginning to suggest an alternative referred to as “salvage during the trial.” This involves converting to more than one device during the trial period to further delineate responders. The literature does not support this method, and it is not recommended. Ultimately, devices that provide multiple waveforms may address this issue.

Summary

Spinal cord stimulator treatment is rapidly evolving, with several new forms of delivery and new proposed indications for use. There is little information on how this treatment reduces pain, and there is substantial evidence that the original tonic devices provide only partial pain relief and are effective only for a short time. We hope these answers to commonly asked questions will help in cases where life care plans recommend SCS.

[1] T. Simopoulos et al., “Explantation of Percutaneous Spinal Cord Stimulator Devices: A Retrospective Descriptive Analysis of a Single-Center 15-Year Experience,” Pain Medicine 20, no. 7 (Jul. 2019): 1355–1361, DOI: 10.1093/pm/pny245.

[2] N.E. O’Connell et al., “Implanted Spinal Neuromodulation Interventions for Chronic Pain in Adults,” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12, no. 12 (Dec. 2021), DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013756.pub2.

[3] J.M. Eckermann et al., “Systematic Literature Review of Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Chronic Back Pain Without Prior Spine Surgery,” Neuromodulation (Aug. 2021), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.13519.

[4] S.M. Adil et al., “Impact of Spinal Cord Stimulation on Opioid Dose Reduction: A Nationwide Analysis,” Neurosurgery 88, no. 1 (Dec. 2020):193–201.

[5] Reddy et al., “A Review of Clinical Data on Salvage Therapy,” and Adil et al., “Impact of Spinal Cord Stimulation on Opioid Dose Reduction.”

[6] Adil et al., “Impact of Spinal Cord Stimulation on Opioid Dose Reduction.”

[7] E.M. Pollard et al., “The Effect of Spinal Cord Stimulation on Pain Medication Reduction in Intractable Spine and Limb Pain: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Meta-analysis,” Journal of Pain Research 12 (2019): 1311–1324.

[8] Reddy et al., “A Review of Clinical Data on Salvage Therapy,”

[9] V.C. Wang et al., “Explantation Rates of High Frequency Spinal Cord Stimulation in Two Outpatient Clinics,” Neuromodulation 24, no. 3 (Apr. 2021): 507–511, DOI: 10.1111/ner.13280.